Site Specific – Final Blog Post

Framing Statement

Our piece for Site Specific Performance at the drill hall was a piece called Recollection, taking place in a unique location within the Drill Hall, just off the Cosker Suite. The location for the piece was chosen because it was a very unique place with many defining characteristics, the room possessed striking features such as an old door-frame from before the refurbishment of the building and a hatchway in the ceiling that leads to the watch tower above the Drill Hall. These unique characteristics were contained within a room only two and a half meters by seven, with one half of the room lowered by a few steps, creating a smaller enclosure within the already small space. The piece began with a guided tour, our single audience member would be escorted to the collection by one of the performers, who would engage the audience in conversation about the Drill Hall, and offering a toffee as an icebreaker to relax the audience for the one-to-one performance. Our piece was centred on memories, hence the name Recollection, the performance we gave was one of museum curators, the small room was our collection showcase, and the size of the room contributed to the performance to create an intimate atmosphere. The Collection contained items, some very old and some very new, these items were the centrepieces of stories, and the objects of myths and legends surrounding the past of the Drill Hall, the stories were based on historical facts of the Drill Hall, some were directly true and others were fictional scenarios based on historical aspects of the space. This performance was heavily inspired by Michael Pinchbecks Long and Winding Road, a piece which itself was a one-to-one performance based around sharing memories in an intimate setting. Intimacy was a large aspect of the performance, the room was set to have a lowered light level, relaxing music playing, and movements from the performers were delicate and calm to add to the visual experience. Delicacy was a large part of the performance, the intimate situation with the performer and the audience member is also shared between the objects the audience would choose. An Audience member was directed to choose pieces that stood out to them. The pieces changed with every audience member as they chose objects they felt a personal connection to. They were asked about why they had chosen the object and invited to handle the chosen object whilst wearing nylon gloves. The objects were handled with reverence and care by the curators and the audience were told the stories whilst holding the items themselves. We feel this increased the connection they were feeling to the stories we were telling as they could feel the real touch of the object, this physical connection to the stories and objects was a key part of the intimacy of our piece. The piece concluded with a return tour, in which the audience member was asked to share their personal memories of the drill hall whilst being returned to the reception desk, this closing conversation was used to maintain control of the schedule for the performance and round off the experience by bringing it back to a personal level with the audience member, to make them realise that they were as much a part of the Drill Hall’s history as the stories we had told them.

Process.

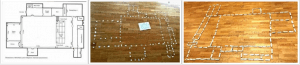

Our piece has undergone huge changes since its original conception, the initial idea had been to utilise the rooms’ unique layout to create an installation piece. The layout of the floor has a walkway of approximately three by two metres overlooking a lowered end section that completes the room, the two sections are separated by a barrier at chest height that divides the room in two and creates the image of a showcase within the room. This space was seen by the group as being the ideal spectator zone for an installation piece, the piece we were interesting in creating was based around the histories of two Lincoln born soldiers who were honoured with the Victoria Cross for their services during the war, and the commemorative plaques are laid outside the Drill Hall.

The original concept for our performance was to be the installation of two dressed mannequins to represent the two soldiers, stood in the lowered section of the room. The mannequins positioning and the setting of the room, which was to be dimly lit and silent, would contribute to the mannequins’ presence and ideally would have created an impressive physical presence. This idea morphed into an idea based around using the rooms’ layout to help us create a realistic trench within the space. This change had come about after a group outing to the Lincoln Archives. At the Archives we found a vast amount of information about the two soldiers we were interested in. This information came in the form of archived newspaper articles, a letter sent to one of the soldiers, and a poster endorsing Mackintosh’s toffee.

The newspaper articles were very informative, depicting the acts of heroism carried out by Leonard Keyworth and James Upton. The main element of the performance was that the audience member would be introduced to the dark room, and be invited down into the lowered section of the room that formed the trench. The stories of the soldiers were to form the basis of the scenario that would play out from the moment the audience enters the trench. The enclosed space was fantastic for having the performance full of sound, the pinnacle of the piece was a soundscape in which the audience would be taken to the ground and sheltered from falling mortar shells, the sound was created during test runs using very large wooden and metal beams and banging them on the floor, screams and shouting of the performers and terrified audience members alike, and a speaker providing believably loud mortar shell sound effects. This iteration of our performance was based around using a combination of the darkness and storytelling to create intimacy, and the soundscape to create the intense atmosphere of a huge event within a small space.

The final re-imagining of our piece saw the most drastic transformation, the idea of creating a realistic warfare scenario in the space was deemed a monumentally difficult task and this revelation led us to observe the space in a different manner to the previous performance model entirely. Our new imagining of the piece was centred on the quiet and removed feeling the room made its occupants feel and we decided to utilise this aspect of the room to create a space that seemed surreal and detached, yet still very connected to the Drill Hall. We had decided to change the performance to one-to-one at this point. Intimacy was a huge part of our performance and we found that in such a small room it was ‘necessary to only have one audience member to allow them the emotional freedom to have their experience’ (Zerihan, 2009) We had found in previous iterations of the performance that audience members would be hesitant in expressing reactions and feelings on a personal level with more than one performer and audience member.

Our new idea was to host a collection of lost and found items. These objects would be the core of our piece. ‘Objects stimulate action, facilitating interaction and exchange’ (Pearson, 2010), this quote formed the basis of our new idea of this performance, the objects would be the main component of our performance, the natural inquisitiveness of the audience would draw them to the objects.

This change was inspired by Michael Pinchbeck’s Long and Winding Road which was also a one-to-one performance in a small intimate setting, in this case a car. This performance was similar to our new concept in that both were about a connection between people and objects. We took inspiration from the method of delivery used in this piece, The tone of spoken word was one we wanted to utilise in our piece as it came across as calm and soothing but still informative and engaging.

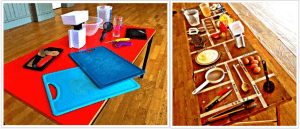

These objects were a random assortment of found items, props and personal possessions, these objects took on a new life during our performance. ‘Objects are unstable, serving representational, decorative, functional, fictive or cognitive purposes, moment by moment.’ (Pearson, 2010)The stories we had available for each object was interchangeable, based on the audiences reaction to the objects the stories would be edited and told differently to enable the objects to serve different purposes in the metanarrative of the Drill Hall. We decided to physically ‘separate’ the room from the Cosker Suite and have the audience enter only through the elevator, as if it were a conduit to a different place entirely. From here we decided to make the space as relaxing and intimate as possible, the lighting in the room was dimmed to half-light to remove the glare from the garish overhead light and diminish the distracting ugliness of the modern plasterboard wall in comparison to the original brickwork wall. The lighting softened everything in the room and made a dark cupboard space seem more inviting and accommodating. Sound was a large part of what we wanted to incorporate in the new idea for the performance. The space was aesthetically pleasing in itself when it was set up, but the silence of being sealed off from all other areas of the Drill Hall was detracting from the performances intimacy. Soft piano music was chosen (namely Ludovico Einaudi’s – I Giorni, Primavera, and Divenire) that was repetitive to a certain degree to allow for comfortable listening, but not to be distracting to an audience member, this was an important aspect in our music choices as music appeals to an audience but we did not want the audiences focus to shift to the music at all.

The room was dressed more erratically for the final re-imagining of our performance, we happened across a stack of carpet samples of all sizes and colours and decided to carpet the lowered end of the room with the thicker and brighter of the carpets, aside from being a pleasant aesthetic the design choice also proved favourable to test audience members who said the room felt much more comfortable and relaxing with the thick carpet under their feet. The room layout was meticulously laboured over, we worked to create a comfortable environment that would not leave the audience member intimidated by the presence or the placement of the curator in the room. We found that test audiences preferred to sit facing the old brickwork wall whilst in the back left corner of the room. However when the Curator was sat in his chair diagonally opposite them the test audience often complained of feeling intimidated by being blocked from the exit by the curator. After considering the layout of the room we decided to change our layout and remove the table from the centre of the room, placing all of the objects on to an old, brass, three-level serving tray and allowing the Curator to take a much less intimidating position with his back to the opposite wall to the Audience member, allowing personal space between the curator and the audience, but maintaining close enough proximity to be able to speak softly and still be heard with proper enunciation and diction. This new arrangement was approved by our test audience members who agreed the space felt more open and comfortable in the new arrangement.

The Audience were to be allowed to touch the objects and become more intimate with the performance on a physical level. This was to allow the audience member to experience our performance through a different sense to just having to look and listen. We would ask the audience members why they had chosen particular objects and draw their focus to particular details before telling them the story of the object. Our piece was about the historical connection between people, objects and the Drill Hall, and after the tour section of our piece had finished the final walk back to reception would be left to round off the experience. The tour guide would ask questions about how the audience member had felt in the space, what their favourite object had been, and why it had stood out. This was inspired by the following quote, ‘Our encounter with objects in space forces us to reflect on ourselves’ (Morris, 1993). We felt that the audience member would feel in a state of recollection after our performance, and so we pursued that line of inquiry with the audience to find out how our performance was being reflected on.

Piece Evaluation

The process behind our piece was a running order of fifteen minutes per performance. This fifteen minutes was broken down further into ten minutes for performance, with two and a half minutes either side for retrieving audience members from the front desk, and walking them back at the end of the piece. This strategy was very useful to us as it enabled us to have complete control of the space we were performing in and enabled us to manage it effectively. This system had its drawbacks with scheduling that left some performances with slightly rushed finishes due to improper time-keeping, however as we remained on-track and didn’t miss any audience members booked slots I would say I found it an effective method of controlling our piece and managing our time.

As the tour guide who walked up the audience to the performance I found introducing myself and the piece rather simple, and enjoyed the introductory conversation about Leonard Keyworth and James Upton, which was well-received by all audience members I bought up personally. Some audience members declined the offer of toffee on the way up to the piece, but as this was an inevitability at some point I did not find this wholly distracting, instead simply mentioning that we offer the toffee as a standard on the tour due to the aforementioned connection between toffee and the Drill Hall. The conversational aspect of the introductory role was very pleasant to carry out and I am satisfied with the manner in which I accomplished the task, however I found that I would have difficulty addressing the audience whilst walking through other groups pieces because of the activities in those spaces, however I do not feel that this detracted from this particular part of my performance.

As the Curator of Recollection I found the role to be very satisfying to portray. Audience members responded well to the professional yet calm tone I spoke with through the performance as well as relaxed and calm body language. This section varied massively from show to show, some audience members would eagerly pick vast swathes of objects to hear the stories of, whilst other audience members took their time, observing the collection and selecting objects after careful calculation. Either route the performance took turned out different results, I found that when audience members were less inclined to select multiple objects I was incorporating other objects into the stories by improvising connections between aspects of the Drill Hall , which the audience members seemed to take well to, enjoying the seemingly random progression of the story through our collection. The first of the two classifications of audience member were considerably harder for me to handle. I had become accustomed to the audience members carefully picking objects and having a brief period of time to prepare as I saw them make their choice, certain audience members were not so hesitant and I was, on only a couple of occasions, mentally unprepared to tell particular stories, rendering me hesitant to declare anything until I had checked our guide.

If I could change one particular aspect of our performance it would have been the process of bringing through audience members. Even though this worked well and enabled us to keep control of our space and manage the performance times it became delayed at one point and we had to make up time by starting the next performance immediately after the preceding one had ended, putting us under time pressure and forcing us to rush some stories, detracting slightly from the overall atmosphere of the performance.

References

Dobkin, J (2009) Study room guide: One to one performance. [Online] Available from http://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/resources/catalogue/rachel-zerihans-study-room-guide

[Accessed 6th May, 2016]

Morris, R (1993) Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, London: MIT Press

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Zerihan, R (2009) Study room guide: One to one performance. [Online] Available from http://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/resources/catalogue/rachel-zerihans-study-room-guide

[Accessed 6th May, 2016]

Pinchbeck, M. (2004). The Long and Winding Road – One-to-one performance. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yz6hpT-4CxE [Accessed 10 Apr. 2016].